Forms of Devotion — a cross-cultural mission to spread faith in images (Madhusree Chatterjee)

New Delhi Indian spiritual art — the earliest genre of visual exposition of life since the beginning of civilization nearly 5000 years ago — has been building bridges across cultures, philosophy, livelihoods, people, traditions and religious beliefs for millennia with invocation rituals around the icons and motifs expressed in this oeuvre.

Over the centuries, spiritual art has become the representative symbol of the progress of religious schools of thoughts leading to new and complex belief systems from the Vedic-era animism to the late Bhakti (devotion)-age iconography of gods and goddesses. The pan Indian religious ideals spanning Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Christianity, Islam and Sikhism— together with epics like the “Ramayana” and “Mahabharata” integrate with the core iconography of Hinduism to form what is today defined as the “Indian sacred art”.

Over the centuries, spiritual art has become the representative symbol of the progress of religious schools of thoughts leading to new and complex belief systems from the Vedic-era animism to the late Bhakti (devotion)-age iconography of gods and goddesses. The pan Indian religious ideals spanning Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Christianity, Islam and Sikhism— together with epics like the “Ramayana” and “Mahabharata” integrate with the core iconography of Hinduism to form what is today defined as the “Indian sacred art”.

The multiplicity of icons in the divine pantheons in turn has added teeth to spiritual art as a mature mainstream genre with “highly nuanced drawings, compositions of scales, stylizations, abstract iconographies and advanced art practices in a variety of medium and regimens – varying across physical terrain of the land”. The thread bindings the different traditions of Indian spiritual art is beauty — a lyricism, figurative complexities, rhythm and refined story-telling that is rarely found in other genres of Indian art. Mythology and epic are its sustenance.

Over the millennia, Indian spiritual art has travelled across the world to spread the spiritual gospel of Orientalism — but found an “empathetic” audience only in the last 100 years with the western art lovers and collectors appreciating the worth of the genre as a “mainstream collectible” for “visual display” in the high art space.

“Forms of Devotion”— an exhibition of 200 works of spiritual art by 100 artists curated from a collection of more than 1,000 art works by curators Sushma K. Bahl and Archana Bahl Sapra from the Museum of Sacred Art in Brussels — opened to a sneak preview in the national capital in the run-up to its formal inauguration at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for Arts (IGNCA) in January-February 2015.

The exhibition – featuring traditional spiritual expressions in multi-media and contemporary canvases — is at the heart of a festival of Sacred Arts in India that plans to bring back home genres of art that are “gradually losing their pre-eminence” amid the contemporary and new media arts movements in India.

Spiritual art in India has been struggling to find space in the country’s new artistic stage occupied with “universal themes of internationalism” and rendezvous with new technology to make the indigenous movements cutting edge and global.

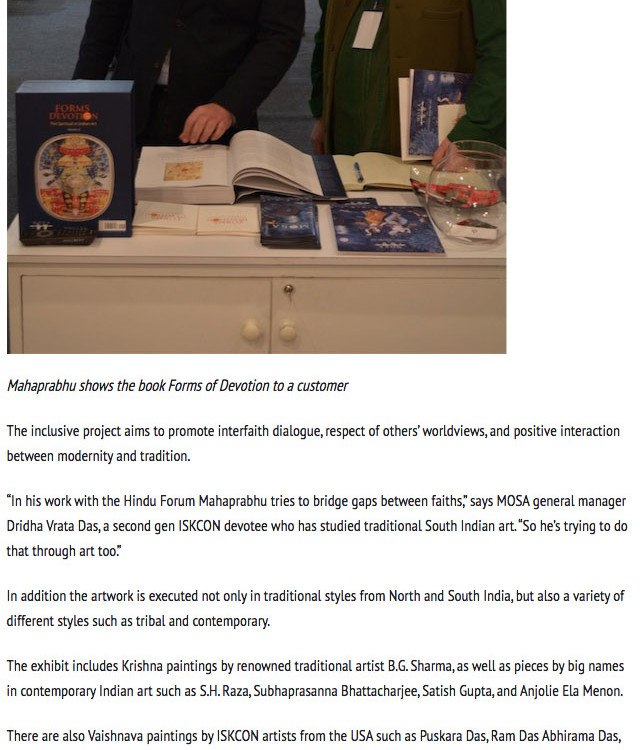

“Art and spirituality are building many bridges between different art forms in India – opening inter-faith dialogues in many different ways. The Scared Art Project began in 2009 with a museum that I set up in Belgium with a focused collection of works from different spiritual streams of practises of India like Hinduism, Vaishnavism, the Shaivaite tradition, the miniature spiritual art of Mysore, Rajasthan and Mysore — created by contemporary artists who have keeping the sacred arts alive for generations through a combination “of the use of traditional imagery and its integration with new techniques and mediums,” says collector Martin Gurvich, who manages MOSA (Museum of Sacred Arts) in an 11th century chateau Louxemburg in Belgium, owned by the International Society for Krishna Consciousness.

Gurvich, the son of a Uruguayan artist of Jewish origin who settled in Europe, is a Krishna devotee inspired by the ISKCON movement.

Gurvich, the son of a Uruguayan artist of Jewish origin who settled in Europe, is a Krishna devotee inspired by the ISKCON movement.

His collection is grounded in his spiritual belief that India “represents the purest and the most plural form of faith that is at once inclusive, diverse and emancipating”. “In the first phase of collecting, I concentrated on the traditional aspects of faith and lot of tribal arts. But curator Sushma K Bahl opened my eyes to the contemporary aspect of spiritual art in the Indian context,” Gurvich said.

The collection is hosted at Chateau de petit Somme, christened as Radhadesh — after Krishna’s muse— a sprawling heritage home owned by Gozelon de Montaiqude, who plundered the abbey of St Hubert. After his death, his wife returned it to the abbey as an act of penance —after which it has passed down several owners till the Krishna cult acquired it as a retreat in 1979.

“The beginning museum is in the fact that several Vaishnavite paintings adorned the walls of the chateau for the last 30 years. They were original art works inspired by ancient Vaishnavite texts, realistic and classical in style. The idea was to build a dedicated space where the cultural roots of the JInfdu JIndu sacred art and its broader connection to the world outside could be studied,” Gurvich said.

Offering insights into the concept of the exhibition and the festival— being described as the first of its kind in India, curator Sushma K, Bahl says “India is a multicultural world, a plural society with multiple voices, identities, ideologies, cultures, faiths and denominations —many ‘India-s’ in one”.

Its eclectic and fascinating mix of arts — essentially meditative, ethereal, spiritual, and assimilative, developed to a high level of sophistication that permeated its socio-cultural milieu that continues to be inextricably intertwined with life — from birth to death.

“The multi-dimensional project — Sacred Arts Festival — conceptualized around the notion of devotion and sacred, explores the theme through artistic creations in varied genres, from across faiths and different regions of India, in varied media, modes and manifestations- all recently created. It presents many facets of Indian art, its mystique and philosophies in today’s global context.

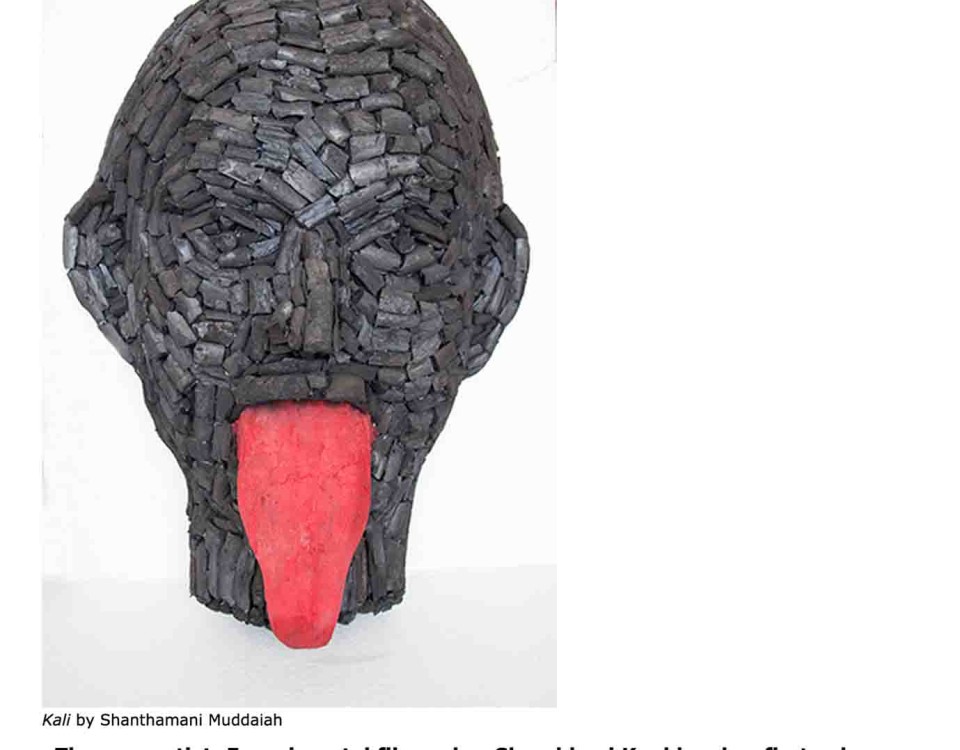

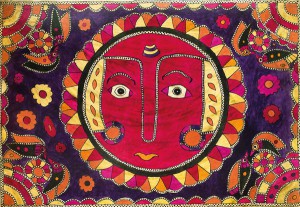

Reflective of this ethos, “Forms of Devotion”, is a large, inclusive and holistic exposition that celebrates the “multiplicity, diversity, creativity, and vibrancy of devotional art of India in varied hues and forms, curator Sushma K. Bahl said. The creative mosiac of the works that have been commissioned for the exhibition is a strange combination of “contemporary abstraction, expressionism and religious content that address larger issues relating to spirituality and society like — secular faith, environment, Dalit discrmination in Hinduism, deconstruction of popular icons to speak of new realities and continuity of living spiritual traditions.

Reflective of this ethos, “Forms of Devotion”, is a large, inclusive and holistic exposition that celebrates the “multiplicity, diversity, creativity, and vibrancy of devotional art of India in varied hues and forms, curator Sushma K. Bahl said. The creative mosiac of the works that have been commissioned for the exhibition is a strange combination of “contemporary abstraction, expressionism and religious content that address larger issues relating to spirituality and society like — secular faith, environment, Dalit discrmination in Hinduism, deconstruction of popular icons to speak of new realities and continuity of living spiritual traditions.

“In an inter-disciplinary experimental mode, the collection comfortably floats between the local and the global, the old and the new; as it transcends various faiths and genres — figurative, mythological, abstractions, Hinduism, Buddhist, Jain, Christian, Muslim, Sikh, Zorastrian, Sufi and Zen. As a continuum and popular resource, with multiple philosophical layerings, created for rituals and offerings, adornment and celebration, be it ascetic or ornate, mystical or provocative, rural or urban, old or new, bazaar art or high end creations, local or global; the assemblage includes representation of icons, epics, and ideas, in art interwoven with life,” the curator said.

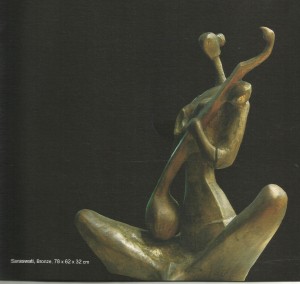

There are two-dimensional works such as paintings, drawings, collage, digital work and photography for the walls, but also “sculptures, installations, videos, films, sound, and interactive, site specific, and mixed media works amongst others”.

The collection encompasses research based and conceptual art that explore the theme from different socio cultural-philosophical perspectives. Contextualized in the history, philosophy and ideology of the culture they stem from, the works reflect the depth and substance of devotional and sacred Indian art imbued with pleasure, meditation and reflection, Bahl pointed out.

The project features over 200 works by some 150 artists – some “renowned masters and others emerging ones from across the country. There are some enormous works and some in miniature format, in varied media and modes — “exploring encounters and dialogue”; between ‘continuity and change’ and between “bhakti Shakti and Chintan”.

The traditions of spiritual art in India trace their origin to the early Vedic age with Shavite symbols and nature icons on rock faces, natural surfaces and palmyra manuscripts. Visual interpretations of the myths and the Vedic lores were important documents of India’s early scared arts.

Pigments on Paper 58×82 cm

It evolved over centuries into the Gandhara School of Art – of religious importance – along the silk route of India, Orient and central Asia. The Gandhara School of art painted its canvases around the Shiva-Shakti and Buddhist visual imagery. The arrival of Vaishnavism in the later Vedic age inspired the artists with stories of the 10 avatars (manifestations) of Vishnu, the churning of the oceans to create the pantheon, the war between the gods and the demons and the epics.

The sacred arts thrived on royal patronage in the subsequent era — beginning 10 century (CE)— commissioned by the Hindu kings and later by the Mughal rulers.

Spiritual art drew its life vitals from the temples and epics. The sculptural friezes on the temple art were the earliest examples of sacred art in India- the best examples being the Nathdwara Temple in Rajasthan, the Vishnu and Shiva temples of South India and the Buddhist shrines in north, northeast and eastern India.

One of the most interesting aspects of sacred arts is its practitioners. Over the centuries, the traditions have been handed down the generations of artists — who have improvised to carry forward the genre. This journey has seen new generations of artists who have been influenced by local, foreign and contemporary movements to create a new idioms of sacred visuals around ancient themes to convey contemporary ideas of faith.

-Madhusree Chatterjee

http://madhu-madhusree.blogspot.in/2014/03/forms-of-devotion-cross-cultural.html